Lessons From the Implosion of Long Term Capital Management

How did a darling hedge fund managed by PhDs and Nobel Prize winners end up imploding in spectacular fashion, threatening the collapse of the entire financial system in the process?

Much of the information in this post was sourced from When Genius Failed by Roger Lowenstein — an account of the decline of Long Term Capital Management, and a fantastic and thrilling novel. I highly recommend giving it a read.

Introduction

“It’s fascinating in that you had 16 extremely bright, I mean extremely bright people at the top of that. Among their top 16 people the average IQ would probably be as high or higher than any organization you could find.

They individually had decades of experience and collectively had centuries of experience in operating in these sort of securities, and they had a huge amount of money of their own up, and probably a very high percentage of their net worth up, in almost every case.

So here you had super bright, extremely experienced people operating with their own money. And in effect on that day in September, they were broke.” — Warren Buffet

Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) was once the crown jewel of America’s burgeoning hedge fund industry. They had a secretive and seemingly impenetrable strategy, a team of partners with accreditations ranging across academia (including two Nobel Prize winners), connections with every major bank on Wall Street and investment from many others, and for a few years, a truly fantastic investment track record. They were making 20-40% annually with seemingly no volatility, no losing periods, a strategy that seemed to be risk-free.

Then everything collapsed within a mere few months, with the fund seeing a drawdown over 91% and requiring a capital injection (organized by the Federal Reserve) from its own lenders to the tune of $3.6Bn. Their partners were stripped of 90% of their ownership in the fund (their remaining stake was only barely sufficient to cover their debts), their academic theories called into question, and their legacies permanently tarnished.

So — how did this occur? How does a fund called “Long Term” Capital Management completely blow up within 4 years? How did so many people — the banks, the wealthy investors, the regulatory authorities — let this fund’s sudden collapse threaten the entire financial system? More importantly, how did so many fail to realize that Long Term was doomed to fail from day one?

Beginnings of a Once-Darling Hedge Fund

LTCM was spearheaded by John Meriwether, the man who drove Salomon Brother’s arbitrage unit from a small section within the firm to a relative behemoth that produced over half of the firm’s profits for multiple years straight.

Meriwether had hand-selected a group of traders for this Arbitrage unit, and these traders were very closely knit — oftentimes they would be found going out to dinner together, or golfing on the weekends. As their profits grew within Arbitrage, they began to sequester themselves away from the rest of the firm, feeling that they were better than other traders because they usually made much more money. They were extremely private among themselves, and they began throwing their weight around more often, eventually taking over all of Salomon’s other bond trading operations.

Arbitrage was unique at Salomon Brothers, being the only unit within the firm where traders were compensated partly with a fixed percentage of their gains with the firm’s capital. If they made the firm $50 million at 15% compensation percentage, they could walk away with a cool $7.5 million. Think about where the incentives lie here — if there isn’t a corresponding “pay us 15% of your losses for the firm,” then this setup only incentivizes risk-taking behavior on the upside, which can be dangerous.

Meriwether left Salomon Brothers after he was essentially forced to resign in 1991, after a trading related scandal — one of his traders in Treasury bonds had submitted a false bid to the US Treasury to take an unauthorized share of a government bond auction, very much against the rules. Meriwether essentially covered for this trader (though he did take the matter to his higher-ups), but it was later revealed that the trader in question had broken multiple other rules as well.

The Treasury and the Fed were furious — Salomon’s then-CEO was forced out, along with Meriwether. Meriwether’s traders defended him to no avail. Even Warren Buffet, acting as interim CEO for the firm, tried unsuccessfully to save Meriwether’s position.

Meriwether wanted to replicate his success within Salomon’s Arbitrage unit, but in a way that gave him much more control with a much larger stake in the profits — so, he started a hedge fund, founding Long Term Capital Management in 1994. Many of his traders from Salomon’s Arbitrage unit came to join him.

Past those he worked with at Salomon, Meriwether recruited academics — many of them being professors at prestigious institutions like Harvard. Two of them, Scholes and Merton, were Nobel Prize winners behind the legendary Black-Scholes implied volatility model. They even recruited a former US central banker.

LTCM raised more capital at its start than any fund had before, just over $1Bn, and the fees they charged were much higher than the typical range for the time period. Despite their very high fees, they seduced investors with a shiny academic veneer and a good deal of smart marketing.

Back then people saw the fund as a sort of magic. The partners were generally very secretive, and details about the fund’s actual trades were difficult to find. People just assumed that these PhDs and mathematicians with their statistical models and probability distributions had cracked the code to untold riches, and they were loving it.

“They [Long-Term] are in effect the best finance faculty in the world.” — Institutional Investor, When Genius Failed

LTCM enticed investment from many different places — The Swiss Bank UBS, the Italian Central Bank, Brazil’s biggest investment bank Banco Garantia, Nike executives, the CEO of Bear Stearns (which ended up clearing many of the fund’s trades), various wealthy individuals, the fund’s own employees and partners, and a great many others.

A Risky Strategy, Perceived as Safe

What LTCM was actually doing, at least in the beginning, was arbitrage — a technique you’ve probably heard of before, but what does it actually entail? Arbitrage is in theory a low-risk strategy that entails taking advantage of pricing discrepancies of assets between two or more markets.

FTX, the infamous crypto firm that blew up a few years ago, got started in part by running a Bitcoin arbitrage — they’d buy Bitcoin for $10,000 in the US and sell it for $15,000 in South Korea, earning a risk-free profit in the process. This is one of the vanishingly few examples of pure arbitrage, where all you are exploiting is pricing discrepancies between identical assets in different markets.

LTCM wasn’t actually running a pure arbitrage, as there are almost no examples of these trades that actually exist in the real world (these days anyway). The FTX example above is one of a scant few examples of pure arbitrage I’ve ever seen.

Instead, LTCM was running statistical arbitrage, or stat arb — not exploiting price discrepancies between identical assets, but instead in assets that are expected to trade within specific bounds in relation to one another.

One example of this strategy as employed by LTCM was credit, or bond arbitrage — the fund would find two bonds that historically traded at specific yield spreads with respect to one another, and whenever the spread got tighter or further apart than expected, they would bet on the spread to narrow or widen to make a small profit.

Bonds with lower yields carry lower risk in the eyes of the market, and generally, US treasury bonds are and have been among the lowest risk bonds on Earth. Say, the yield on a 10 year treasury bond is 4%, and the yield on a particular investment grade corporate bond is 4.5% — this is called the investment grade (IG) spread. The spread is the difference in yield between the corporate bond (yield being a measure of perceived risk) and the treasury bond (often perceived as riskless).

If the spread between two bonds was typically between 0.45% and 0.6%, but suddenly expanded to 0.7%, LTCM would buy the higher-yielding bond and sell the lower-yielding bond simultaneously, before reversing the trade when spreads narrowed back to their typical levels.

When a trade like this is put on, short one bond and long another within their specific spread ranges, you make or lose money purely by changes in the spread. You’re insulated if both bonds decline or rise simultaneously. If you bet on spreads to narrow and they narrow, you make money. But if they instead widen, you can lose money.

A single trade here is generally only going to make a tiny profit — as the fund’s own partners put it when they went to raise capital, they were “picking up many nickels out of thin air.” Many nickels, but still only a nickel at a time — not much money per trade.

If you have a bunch of usually safe trades that make very little money per trade, how can you generate any meaningful returns? Leverage. You could, for example, borrow 30x your own money to place your trades, significantly juicing your returns in the process. That is precisely what LTCM did.

They employed statistical arbitrage, a strategy that is never guaranteed to work, only expected to work, at 30x leverage. You’d be right to assume that such a strategy is completely unsafe and would certainly lead to total destruction over a long enough timeframe.

“99% of the time it works. But 83.3% of the time it works to play Russian roulette with one bullet in 6 chambers. Neither 83.3% or 99% is good enough, when there is no gain to offset the risk of loss.” — Warren Buffet

If you happened to be running these trades with 30x leverage and you suddenly have to sell when these trades are going against you, you have the potential to lose much more money than you could ever hope to repay, much more than you ever stood to gain in the first place. [Sometimes, foreshadowing is relatively obvious].

Even Riskier Strategies

This credit arbitrage strategy worked for a few years. The fund had very little competition initially, and the pickings were great in markets across the world. LTCM made 21% in its first year, 43% in its second, and 41% in its third — truly fantastic returns.

But as others caught onto their success, competitors started running the same trades. This meant that spreads were generally more efficient — more market participants means higher efficiency, and lesser opportunities for those trying to exploit inefficiencies. In their fourth year, LTCM made just 17%, which was the average for all hedge funds that year. They had effectively lost their edge within credit arbitrage.

Seeing their opportunities within credit arbitrage diminish, LTCM started pursuing other strategies, such as risk arbitrage (also called merger arbitrage). Essentially here, you are betting that a proposed merger or acquisition either does or does not pan out, and to get any decent returns here, you generally need to take a view that is significantly different from the market implied odds of the deal being completed.

Let’s say company ABC wants to acquire company XYZ for $100 per share. XYZ is currently trading at $90 per share. The difference between the market price of XYZ and the proposed acquisition price represents the market’s uncertainty about the deal going through. If everyone knew the deal was going to clear, XYZ would already be trading at $100, or very close to it, because everyone knows their shares in XYZ will be bought from them by ABC for $100. In this example with XYZ at $90, the market gives an 11% chance that the deal won’t close, so you could make 11% betting that it will.

Typically with these trades, one will short the stock of the acquiring company (as making the acquisition either removes cash or adds debt to the acquiring company) and buy the stock of the company being acquired (as the acquirer is willing to buy shares of that company higher than the market price). I’m oversimplifying here, but you get the general idea.

LTCM ended up trying their hands at many of these trades, almost rapid fire, very willy-nilly. They did not specialize in merger arbitrage, which is in itself a very specialized and risky style of trading — if you don’t have a 40 year career in M&A law, you’re going to be at a disadvantage against many others playing the same trade. So at this point, LTCM was trading a lot of these securities without any real edge.

Eventually, LTCM turned towards outright speculation, across all kinds of asset classes including stocks, bonds, and a special new product known as 'equity volatility.’ These days, equity volatility is a fairly common thing to trade, at least for more specialized investors or institutions. Technically, anyone over the age of 18 in the US can go open a Robinhood account and bet on equity volatility with VIX calls or puts, as the VIX is an index of volatility on S&P 500 equities.

Back in the day though, equity volatility was a much rarer beast, and only a handful of firms could actually complete trades dealing with it. The market was not nearly as developed as it is today, which means it was less liquid, and more risky.

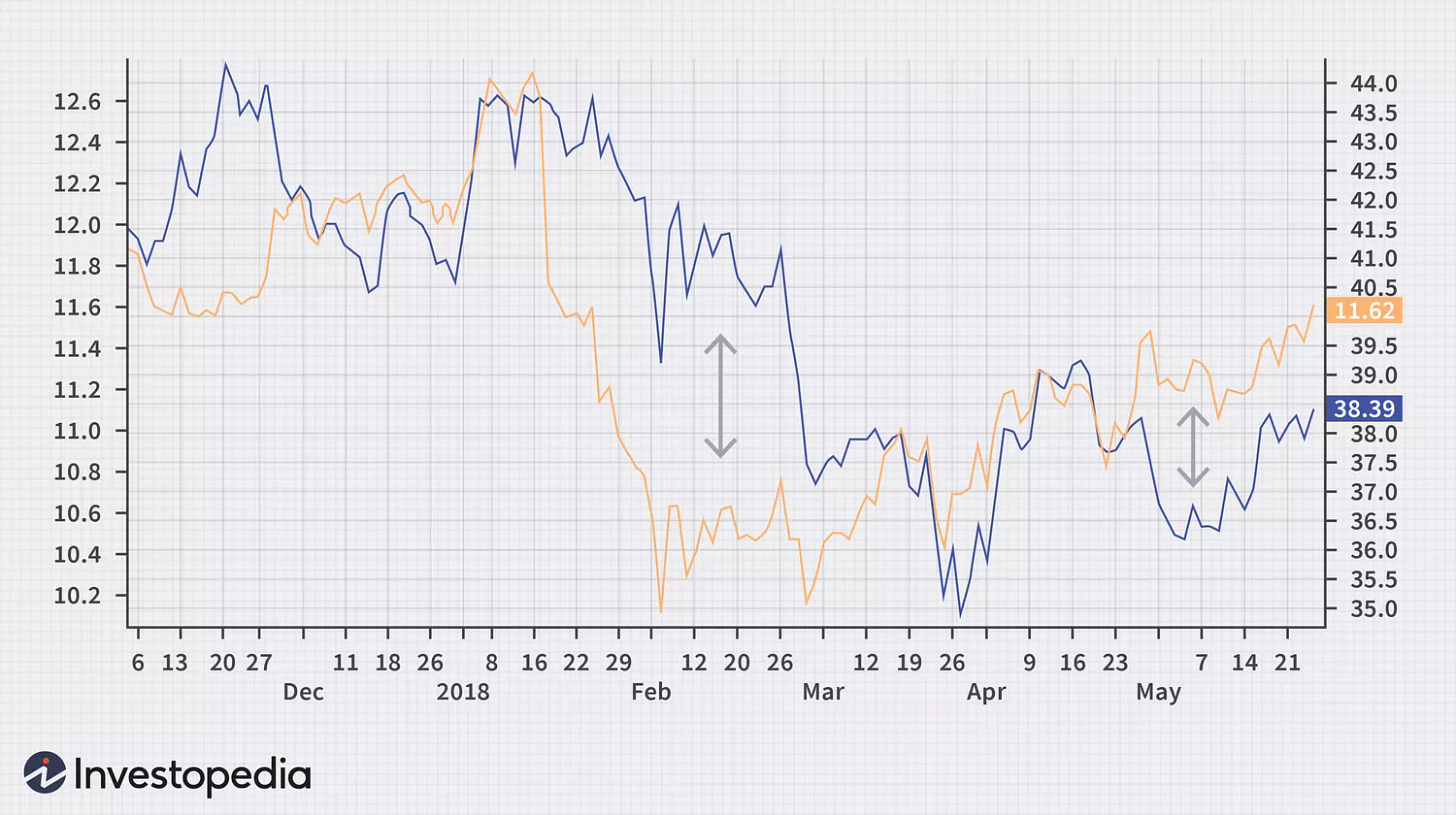

Volatility is mean-reverting over a long enough timeframe. Here’s a chart of the VIX over the past 9 or so years. Notice the big, sudden spikes, before the VIX falls back to its 10-year average (mean), around the blue line there. If volatility is elevated, you can effectively sell it to others and bet that it will return to its average, or likewise buy volatility when it appears underpriced relative to its average. Again, I’m oversimplifying, but these are the basic concepts. LTCM was effectively short volatility, betting that it would decline back to its average, as it always has over a long enough timeframe.

Another interesting thing about equity volatility, as opposed to other ‘commodities’ like silver or gold — volatility isn’t a physical product. You can’t store volatility in your attic, or in barrels like oil — there is no physical supply.

In When Genius Failed, Roger Lowenstein brought up a great example of this difference between volatility and other assets. Back in the late 1970s, the Hunt brothers tried to corner the silver market by buying up much of the supply — this sent the price of silver up from $11/ounce to $80/ounce.

Upon hearing that silver prices had rose so substantially, average joes began selling as much household silver as they could to take advantage of the elevated prices. They melted down silver candlesticks, silverware, they sold the silver out of silver dollar pieces, any silver that was just laying around suddenly flooded the market, and prices crashed back down to their expected levels. This sent the Hunt brothers into bankruptcy, by the way.

But there is no physical equity volatility. LTCM was betting that volatility would decline, right as markets began crashing across the globe, which only elevated volatility levels. Because there was nobody rushing to sell this elevated equity volatility, with no physical supply, it could remain elevated far longer than you’d expect from other assets like silver. There was nothing to push volatility back down, so it stayed elevated, effectively trapping LTCM in their trade with no hope of recourse.

Right before it all came crashing down, LTCM was levered 30x, controlling as much as $100Bn in assets with a meager $3-4Bn in equity. They were involved in merger arbitrage, credit arbitrage, and they were short volatility. They were outright speculating in stocks, bonds, equity volatility, and through derivative contracts like interest rate swaps, they controlled a notional value of securities as high as $1 trillion dollars — with just $3-4Bn of their own money on the table.

“And Long-Term had bet on risk all over the world. In every arbitrage, it owned the riskier asset; in every country, the least safe bond. It had made that same bet hundreds of times, and now that bet was losing.” — Roger Lowenstein, When Genius Failed

The Grand Implosion

LTCM’s implosion was brought about by a few sudden economic shocks that caused spread trades to go against them in a big way for an extended period of time. Recall when I mentioned that, with trades like these, you can lose money if spreads widen — if you’re forced to close your position as spreads are widened, you’ll have to sell your trade at prices that are disadvantageous, and realize the loss.

But it wasn’t just spread trades that killed them. Recall how involved they were in merger arbitrage? When economic conditions deteriorate, when markets get shocked and market participants begin to feel fear, suddenly the chances of acquisitions occurring look slimmer, so LTCM also got killed on their merger arb trades.

Not to mention the firm’s exposure to equity volatility — these same economic shocks that killed them in spread trades and merger arbitrage increased equity volatility, hand-in-hand. Long Term was effectively crippled by nearly every single one of their trades going against them at the same time, while they were leveraged 30 to 1, with as many as 60,000 individual positions.

LTCM was a big player in these markets, with their $100Bn in assets and $1Tn in notional derivatives exposure. Right as markets began crashing, people began to sell risk — all kinds of risk, whatever the risk was, nobody wanted to touch it. This caused liquidity to dry up in LTCM’s markets, as nobody was stepping up to buy their positions — in fact, by this point, LTCM’s strategies had been leaked to the broader Wall Street community.

People knew what sort of trades LTCM was in, so they began to sell these trades just because they knew LTCM would eventually have to sell, which would depress the price, and they wanted to get out before LTCM did. At the time, this was known on the Street as the LTCM death trade. Some firms were even buying equity volatility, right as LTCM was stuck holding their stake — firms that hadn’t touched equity volatility before, as it was a thinly traded asset class. Why else would a firm do this, unless they were specifically trying to exploit LTCM’s pain?

“The fund was immobilized by its sheer mass. The smaller fish around it were liquidating every bond in sight, but Long-Term was helpless, a bloated whale surrounded by deadly piranhas. The frightful size of its positions put the partners in a terrible bind. If they sold even a tiny fraction of a big position — say, of swaps — it would send the price plummeting and reduce the value of all the rest.” — Roger Lowenstein, When Genius Failed

All this completely crippled the firm. As every trade went against them, their equity deteriorated to levels that were barely sufficient to post the margin necessary to clear their trades. Their size made it impossible to get out of these toxic trades, and because everyone else knew they’d have to sell eventually, they all decided to get out first, which further depressed prices.

Because the firm was so highly leveraged, they were risking much more than their own money — money from many major banks on Wall Street was at risk, too. This culminated in a bailout led by the Federal Reserve, in which all banks with exposure to LTCM organized a buyout of the firm. This ensured that LTCM could avoid having to liquidate positions at disadvantageous prices, destroying the money lent to them by the banks and threatening the safety of the entire financial system.

The firm’s partners were essentially cut out — their stake in the fund was cut down by 90%, they lost their decision-making ability, and they were essentially forced to watch as the fund was slowly liquidated over the next two years. Many of LTCM’s partners had put their entire net worth in the fund, and they were left with next to nothing. They were completely wiped out, along with many of their employees, and a great many investors.

Doomed From the Beginning

LTCM’s partners and their statistical models were making one key incorrect assumption about markets, being that they behave randomly. If market returns were truly normally distributed (normal distributions are the result of random processes), LTCM might have survived much longer. But market returns are not normally distributed, because market prices are determined by humans who oftentimes do not act rationally — instead, they act in ways that are oftentimes literally impossible to predict.

Humans influence market prices, and humans are subject to emotions that can cloud proper rationality from making the decisions. When it comes to markets, fear and greed are the two classic examples. Because humans determine market prices, markets inherently contain these emotions as well, which makes them behave irrationally.

“In every class of asset and all over the world, the market moved against the hedge fund in Greenwich. Rickards, the house attorney, described it to colleagues as the ‘LTCM death trade.’ The correlations had gone to one; every roll was turning up snake eyes. The mathematicians had not foreseen this. Random markets, they had thought, would lead to standard distributions — to a normal pattern of black sheep and white sheep, heads and tails, and jacks and deuces, not to staggering losses in every trade, day after day after day.” — Roger Lowenstein, When Genius Failed

Many investors in LTCM failed to realize this key aspect of market psychology. They were seduced by an academic veneer, by the notion that these Harvard mathematicians couldn’t possibly make such awful bets. They invested in something they didn’t fully understand, as LTCM was often very secretive and private about aspects of its strategies. In other words, they didn’t do their due diligence, and many of them were punished for it.

Lessons and Takeaways

1: Markets do not behave rationally, and market returns are not normally distributed, they’re not random. They are subject to emotional forces like fear and greed that defy logic and ensure irregularity. Don’t bet on eternal rationality in a system that is definitively not rational.

2: Be careful with leverage. Some will tell you that all great investment track records made use of leverage, which is probably true, I’m not actually sure. Either way, don’t be overleveraged — certainly don’t leverage yourself 30 to 1 like LTCM did. That’s not even really possible these days I’m pretty sure, but still, if you must employ leverage, do it carefully, methodically, and always make sure you have a damn good exit plan.

3: Speaking of exit plans — it’s probably a good idea to make sure you can get out of any trade. LTCM was literally locked into their trades, as there were no buyers for what they needed to sell. Be mindful of liquidity, and the constraints imposed by a lack of liquidity. Liquidity does affect securities prices — you could find a cheap nanocap stock that looks like a great bet, but remember, it’s probably cheap because nobody really big can actually buy it, and even if they could, they couldn’t sell it in any kind of hurry. Is that a good thing, or a bad thing? It depends. Illiquidity could give you a good price on a small but quality company, but it depends on the company. Smaller portfolios can benefit from illiquidity in specific stocks, because there is more likely to be market inefficiency in less liquid markets. But, illiquid positions can be difficult to sell as well, if you need to move on or take a quick loss.

4: Correlations eventually always go to one eventually. During panic periods, people will sell all kinds of risk, around the globe, simultaneously. All markets will crash at once, all risky products will be sold for lower risk alternatives like treasury bonds or cash. Remember that during these periods, markets are not behaving rationally, but you shouldn’t expect them to, either.

5: Only invest in what you know. If you don’t know how a firm is making money, or if you don’t know how a business actually works, save your money and invest in anything else, something that you do understand.

6: Be mindful of fear and greed. LTCM was enormously greedy, in their use of leverage, but also in the fact that their partners had almost their entire net worth in the fund, even after their 40% annual winning streak. It never hurts to take some chips of the table when you’re doing well — nobody ever went broke taking profits. There will always be another rainy day, and if you’re overexposed heading into such a day, it might already be too late for you to save yourself.

We love normal distribution curves because they are so easy to model with computers. But we don't live in a normal world. Maybe log normal. It certainly is a wild world. Earthquakes cause earthquakes. Panics cause panics. Crashes cause crashes. During crises it is funny to watch the inevitable CNBC references to several "X number sigma" events in a week or a one in a million year shock. No no no, more like a half dozen to dozen times each century in our wild world where managing risk isn't as easy as linearly extrapolating the most recent data points to calculate computer driven risk models that predict crises based on how the world works when it isn't in a crisis.